Buffett’s letter, forecasts and recency bias, and the right type of value

The best investment research, blogs and podcasts this week

If you’ve been anywhere near Twitter (and FinTwit in particular) this week you’ll know that Warren Buffett has published his annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders.

Buffett’s letters are a gold mine of investing wisdom (you can find them all here). They’re especially hard to beat on subjects like quality, valuation, moats, compounding and business operations. Over the years they’ve lifted the lid on his mistakes, big wins, and his undying admiration for the American Tailwind.

The latest missive is shorter than normal, and slightly different to what we’ve been used to over the years. That probably reveals something new about the way Buffett thinks these days. After all, he’s 92 years old, and his business partner Charlie Munger is 99. They’re not exactly coasting, but there are definitely signs of a wind down.

Most followers of Berkshire know the transfer of management at the top has shifted from Buffett and Munger to the hands of successors like Ajit Jain and Greg Abel. While the two founders still call the shots, this latest letter feels more reflective than usual.

Gone are the deep dives into performance, subsidiary holdings and operations. Those are found in the much larger annual report. In their place are some simple lessons on why Berkshire’s approach has worked so well and what future investors can learn from it.

Some commentators (like this) have taken issue with the perceived lack of detail. But I think that misses the point.

The truth is that much of the really important groundwork at Berkshire: the smart moves, the stake-building, the learning from mistakes, the patience, the investing in ‘businesses not stocks’ was all done decades ago.

That’s not to diminish the challenge of sustaining performance year in, year out from such a vast base. But that’s a different issue, and increasingly one for the successors to deal with. The hard stuff… the getting to where they are now… that work was done long ago. And that’s really what this letter is all about. It reiterates some of the most important points he’s been making for years:

Invest in businesses, not stocks

Buffett says the aim is to make meaningful investments in businesses with long-lasting favourable economic characteristics and trustworthy managers. The message here is to buy the ‘business’ not the ‘share price’. As he says: “That point is crucial: Charlie and I are not stock-pickers; we are business-pickers.”

Nothing is certain, and luck is important

Despite his focus on picking businesses, Buffett owns his mistakes. He says: “In 58 years of Berkshire management, most of my capital-allocation decisions have been no better than so-so. In some cases, also, bad moves by me have been rescued by very large doses of luck.”

You only need to make a few good decisions

Buffett’s experience shows how a few big winners can transform your wealth. For example,

Berkshire spent $1.3 billion buying shares in Coca-Cola in the seven years up to 1994. That year the dividend paid on those shares was $75 million. Last year the payout had risen to $704 million. As a result, Coca-Cola was, and remains, 5% of Berkshire’s net worth.

Buffett says: “These dividend gains, though pleasing, are far from spectacular. But they bring with them important gains in stock prices.”

The point here is that while the scale of this investment is unthinkable to most of us, the choice of Coca-Cola as a highly profitable long-term business made a big difference over time.

It’s really that final point that sums up the message, not just in this letter but in almost all of them over the years.

Buffett finishes with a quote that will live long in the memory of investors. But it’s actually one that seems inspired by something Peter Lynch wrote in One Up on Wall Street. In that book, Lynch said: “Selling your winners and holding your losers is like cutting the flowers and watering the weeds.”

Buffett takes that imagery further by saying:

“The lesson for investors: The weeds wither away in significance as the flowers bloom. Over time, it takes just a few winners to work wonders. And, yes, it helps to start early and live into your 90s as well.”

It’s as simple as that. A combination of quality businesses, luck and patience - and a very long runway!

Incidentally, for a different view on Buffett and how investors interpret what he has done, there is a great article (written last year) about it here: Uproar Capital - Why Don't More Buffett Devotees Actually Copy Him?

Frustrating forecasts and recency bias

More reminders this week that forecasting is perilous and listening to forecasts is risky.

First some context, here’s a view of the annual price returns from the S&P 500 between 2011 and 2022:

Next is this chart from Vanguard, which plots the 1-year analyst expectations for price changes in the S&P 500 over the same 12 year time period. In other words, each December they were asked for their forecast of where the index would end up 12 months later:

Near term forecasting like this is insanely difficult, but it seems we’re all mesmerised by these kinds of guesses.

The grey blocks represent the range of forecasts for each year

The green dots show the actual price return each year

As this chart shows, three quarters of the time what actually happened didn’t even fall within the range of forecasts. So most of the time, judging what the market will do next year is beyond anyone’s best guess (the article is here).

But dig into the detail and there are other points to take from this:

In five of the years where the market finished in positive territory, even the most optimistic analysts were too pessimistic with their forecasts

In the four years where the market finished flat or down, even the most pessimistic analysts were too optimistic

None of the median forecasts predicted a down year - in all cases the consensus median average forecast was for a positive finish for the index

Across the 12 years, forecasts were very heavily weighted to a positive finish - analysts rarely predicted a negative year

There was another, not entirely unrelated article about forecasting during the week from Joachim Klement, the Liberum strategist - The world’s most common forecasting mistake

He picks up on the risks (often taken) of extrapolating recent events and projecting them in ridiculous ways. He reckons it’s the most common mistake that forecasters in any field make.

As Joachim says, the process of how this happens is pretty standard:

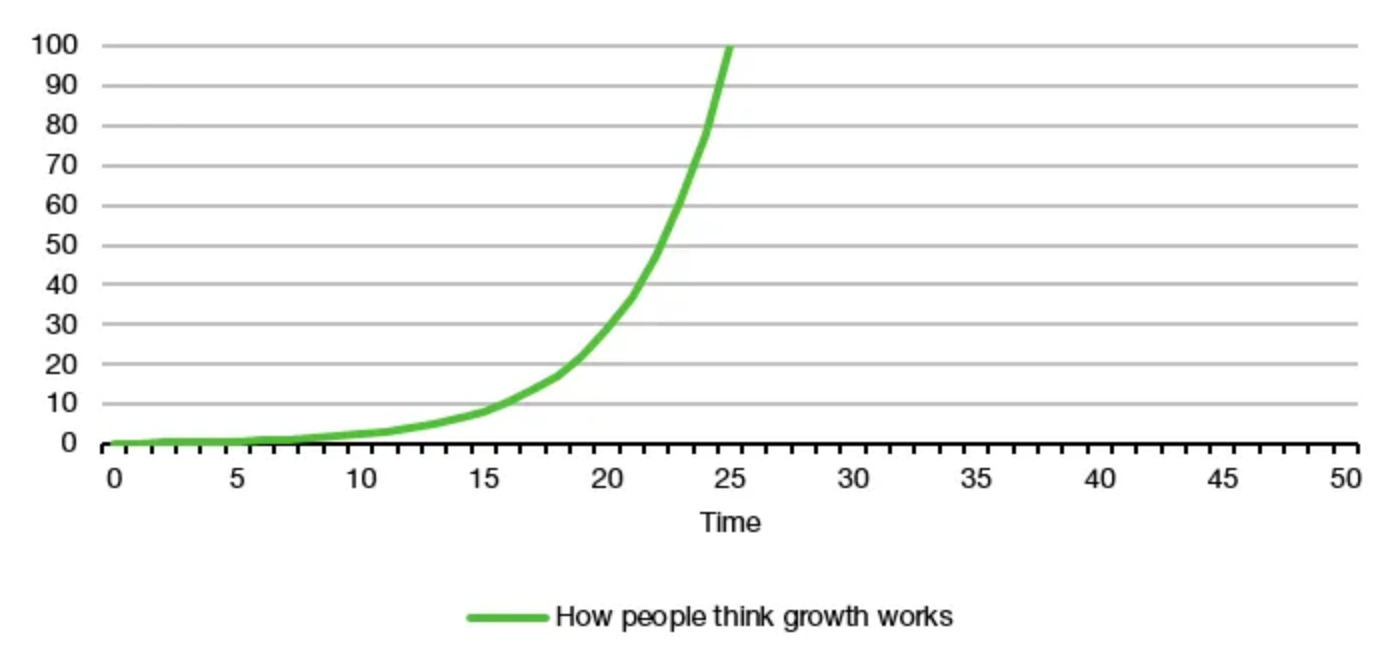

“Typically, the mistake starts by using recent growth rates, then adapting them a little bit to reflect the opinion of the pundit about the future (if the pundit expects growth to slow down, the growth rate is adjusted downward, for example) and then extrapolating that growth rate many years into the future. The result is a projection that looks like the chart below.”

So whether it’s forecasting index returns a year out or the growth of some new industry, it seems that even near term estimates are often way out.

These kinds of errors have been blamed on a catalogue of psychological and emotional errors, ranging from overconfidence to over-optimism. But another major cause is the tendency to obsess about the recent pass… so-called recency bias.

Recency bias crops up all over the place - and not just with financial analysts. A study of betting trends in NFL American Football between 2003 and 2017 found a marked tendency for gamblers to bet on teams that had won their previous games - especially if it had been by a sizeable margin.

You could say that looking to previous winners is not an unreasonable strategy for predicting future winners in NFL football (perhaps the momentum effect is at work there too). The problem is that the bookies know it…

The study found that bookmakers priced their odds accordingly, so they were able to profit handsomely from their punters’ recency bias.

The lesson? Be wary of over emphasising the recent past when it comes to predicting what might happen in the future.

Bargain basement or quality on sale?

‘Cigar butt’ investing in the style of Benjamin Graham and, for a time at least, Warren Buffett has a very solid heritage. It’s the extreme end of value where fortunes can be made but the volatility and patience required mean you’ve got to be made of sterner stuff.

Market conditions since the financial crisis have been generally favourable to growth shares. That left value - and deep value in particular - out of favour for an unusually long time.

But things have changed. Eighteen months of uncertainty have reinvigorated interest in the art and science of detecting value, but which of these styles really works?

Nick Sheridan at Janus Henderson has looked into trends in performance of both ‘deep value’ and ‘quality value’ over the past 20 years in Euro denominated markets (read the report here).

As part of the test, historic price-to-book valuations were used to define deep value. Meanwhile, quality was measured in shares that were “mispriced relative to their balance sheet structure, earnings/cash flows, their retention policy and current rating relative to their assumed sustainable return profile”.

The study found:

At valuation extremes (cheap), deep value outperforms quality value, but only for relatively short periods before it is eroded and surpassed

Quality value outperforms deep value roughly 80%+ of the time for non-financials and roughly 85% of the time for financials

Here is how that looks in a chart:

Sheridan’s study shows that quality value has had a poor couple of years and is trading at levels not seen since 1999/2000.

That supports the idea that value is super cheap in Europe right now - and if you’ve got anything other than a very short-term horizon, it could be worth a closer look.

Thinking & Strategy

Intrinsic Investing

Why Regret and Good Investing Don’t Mix | by Todd Wenning, CFA

The Investor Way

E124 - Steve Daniels Interview (Twitter - @ScroogeMcCodf) - Part 2

E123 - Steve Daniels Interview (Twitter - @ScroogeMcCodf) - Part 1

Monevator

How quickly do bonds and equities bounce back after a bad year?

Invest Like the Best with Patrick O'Shaughnessy

Doug Leone - Lessons from a Titan - [Invest Like the Best, EP.318]

Dividend Growth Investor

Keeping Investing Fees Low Matters

Musings on Markets

Data Update 6 for 2023: A Wake up call for the Indebted?

Of Dollars And Data

The 7 Greatest Asset Bubbles of All Time [All You Need to Know]

Investor Amnesia

A History of Market Panics

Institutional Research

BNP Paribas

Weekly market update – The inflation beast remains unbeaten

Alliance Bernstein

Reimagining Growth: A Market Beyond Mega-Caps

Alpha Architect

Inside the Minds of Expected Stock Returns

CFA Institute Enterprising Investor

The Size Factor Matters for Actual Portfolios

Securities & Markets

A Long Time In Finance

The Pride of Icarus: Neil Woodford's Epic Rise and Fall

AJ Bell Money & Markets

Market rally fizzles, supermarket price wars, energy bill warning and Musk back on top

TWIN PETES INVESTING

Podcast no.95 with LIVE in person video

Money Makers

Weekly Investment Trusts Podcast - Featuring Simon Edelsten and Richard Staveley (25 Feb 2023)

Quality Small Caps

Small Caps Podcast with Paul Scott – Episode 7 for 2023